“It was a wonderful project — all the way through. It’s amazing that we did it — as a community, and even as a small construction company. It helped us put down roots here, and [we made] friendships that we still have. So on that level, it was just great. I think it was a real positive. A real positive for everyone. And it was fun!”

—Bruce Boyd, contractor

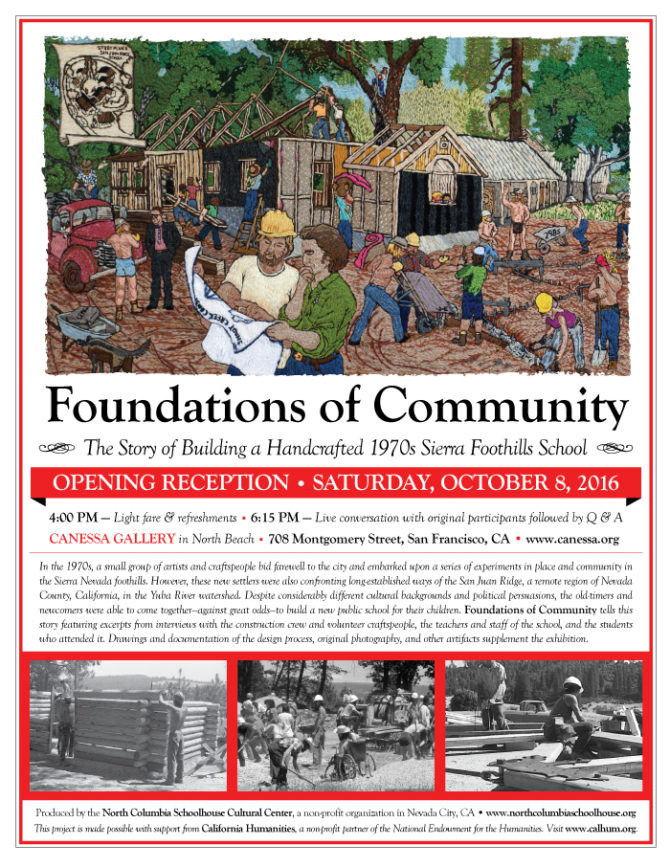

Forty years ago, a story of tremendous depth and courage took place on the San Juan Ridge. Against great odds, residents of this rural part of Nevada County came together to build a public school for their children. With a focus on using local labor and materials, the project was in stark contrast to the increasing industrialization of school construction typical of the time. The school was indeed different as it featured log cabins, handcrafted details, and even a scaled replica of the North Columbia Schoolhouse. Building Oak Tree School recounts this story while also discussing how the school system has evolved since.

Even in the 1960s, one-room schoolhouses built during the gold mining era were still in use at North Columbia, North San Juan, and Birchville, then administered by two different school districts. The Field Act, passed in response to the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, had mandated that all new school construction meet more stringent structural requirements and that existing schools be retrofitted – if feasible – by 1970. As a result, it was determined that these one-room schoolhouses of the San Juan Ridge would have to be phased out of use (the North Columbia Schoolhouse would later be repurposed as a cultural center beginning in 1980).

With encouragement from State officials, the two local school districts decided to merge to form the San Juan Ridge Union School District and funding was acquired to build Oak Tree School (originally named the San Juan Ridge Country School) for kindergarten through eighth grade students. Upon purchasing the site, which featured numerous trees and rock outcroppings, the School Board remained keen on maintaining the qualities of the one-room schoolhouses in the design of the new campus. To execute this vision, the board hired San Francisco architects, Daniel Osborne and Zach Stewart, who had become familiar with San Juan Ridge after designing a house for Gary Snyder in the late 1960s.

Osborne and Stewart were sympathetic to the community’s desire to build a school uniquely suited to the site and a custom curriculum. Instead of designing a monolithic, industrial “pod” school typical of the time, the architects conceived of a school design inspired by the New England continuous architecture documented in Eric Sloane’s book, An Age of Barns, complete with a five-eighths scaled replica of the North Columbia Schoolhouse as an homage to one of the old school buildings the new school would be replacing. Children would rotate between classrooms and outdoor spaces for different activities instead of being in a single classroom.

The School Board also drafted and approved a policy specifically requiring that local labor and materials be used as much as possible so that the project would benefit the local economy where jobs were scarce. However, as a publicly funded project, the construction contract still had to be awarded through an open bidding process.

To achieve the vision of building the school with primarily local residents, Bruce Boyd and Jeff Gold, who had been apprenticing with Osborne and Stewart and actually drafted the construction drawings for the school, became licensed contractors and formed the Shady Creek Construction Company to bid on the project. On a snowy evening in December 1974, it was announced that Shady Creek Construction Company had submitted the lowest bid and was subsequently awarded the contract to build Oak Tree School.

As the construction crew broke ground in early 1975 and prepared to pour the concrete foundations, they encountered a major obstacle. Labor unions from out of the area (there were no unions locally) had decided to conduct an “informational” picket of the job for not using their workers as was typical on most public works projects. As a result, the ready-mix concrete truck drivers would not cross the picket line. Boyd and Gold patiently explained to the union representatives the exceptional nature of the rural construction project – with its focus on employing local workers – to no avail. Faced with the prospect of not having access to concrete, the construction crew made the decision to mix all the concrete on site.

Like ants on a hill, over one hundred volunteers showed up on the site during consecutive weekends in June 1975 to mix and pour the concrete. An intricate system of weighing and measuring using wheelbarrows had been developed to ensure the proper ratio of materials was mixed for each batch.

Weeks later the materials testing laboratory reported that the mix was nearly twice the required strength. With the foundations cured, the framing commenced – using lumber milled at the local mills – and the construction crew gained momentum. Custom details like a stone fireplace for the lodge assembly hall, log cabins, truss plates made out of ornamental iron, and a stained glass window depicting the Yuba River emerged. When it opened in 1976, The school was a collective work of art.

For the next fifteen or so years, the school system on the San Juan Ridge thrived, described by many as a “golden age”. Active parent participation was the norm. The demographics were such that the School District expanded to a new campus for Grizzly Hill Elementary School, which under the stewardship of Brian Buckley was evenutally recognized as a Distinguished School by the state of California.

However, during the mid-1990s, the Charter School movement began to present parents with new and different choices other than the conventional public school. Some parents chose to send their children to Charter Schools, which were opening in “town” (i.e. Grass Valley and Nevada City). Some chose to home school or enrol children at private school. By the early 2000s, with public school enrolment declining, Oak Tree School was no longer in use as a school.

Today, behind the leadership of James Berardi, Grizzly Hill Elementary School is in the process of recovering its lost luster and parental involvement is increasing once again. School choice remains an ongoing question for the San Juan Ridge community. As for Oak Tree School, the hilltop campus of buildings is now serving all ages through a Family Resource Center. The story remains unfinished.

Events about the history of the school were conducted earlier in the spring 2015, including a “story swap” event on the Oak Tree School site between some of the original builders and current school children from Grizzly Hill Elementary School on the San Juan Ridge as well as a separate Open Telling night for others to share their tale. The project also supported an original interpretive art piece by Aram Larsen, which was inspired by the Oak Tree School buildings, and the collaborative creation of a tapestry depicting the narrative of Oak Tree School as part of the ongoing San Juan Ridge Tapestry Project.

This project was made possible with support from Cal Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. For more information, visit www.calhum.org.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of Cal Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.